System Design with ForSyDe-Deep

Alfonso Acosta

2009 Royal Institute of Technology (KTH)

Stockholm, Sweden

alfonsoa@kth.se

Disclaimer and Prerequisites

This document has been devised as a practical hands-on introduction to the use of ForSyDe-Haskell’s implementation. Thus, it is intentionally informal and non-exhaustive. If you are interested in ForSyDe’s theoretical foundations please refer to the ForSyDe website.

In order to take full advantage of this tutorial, it is essential to have a good background in the Haskell programming language. Familiarity with some Haskell extensions (Template Haskell, Multiparameter Type Classes with Functional Dependencies, Undecidable and Overlapping Instances) might help but is not vital.

Installing ForSyDe

ForSyDe is implemented as a Haskell-embedded Domain Specific Language (DSL). As intimidating as the previous phrase might sound, from a practical point of view it only means that, to all effects, ForSyDe is simply a Haskell library.

As it was already stated in Disclaimer and Prerequisites, ForSyDe relies on many Haskell extensions, some of which are exclusive to GHC. For that reason, a recent version of GHC is required to build ForSyDe. ForSyDe has been tested to run successfully on Linux, OSX-Leopard-x86 and Windows when compiled under GHC version 7.0.3.

ForSyDe’s library is available on Haskell’s HackageDB, a popular repository of Haskell Cabal packages. If ForSyDe is the first Cabal package you install or your memory needs to be refreshed in this matter, you should read How to install a Cabal package.

UPDATE: To make things easier, the ForSyDe-Deep package comes with a Stack installer script which takes care of all the intricate dependencies, so you might want to use it instead. For this you might want keep the Stack User Guide as reference. Please refer to the Setup Guide for detailed installation instructions.

At the time being, ForSyDe depends on the type-level and parameterized-data packages to offer numerically-parametrized vectors, and on some other packages normally distributed with GHC and the Haskell Platform.

Introduction to ForSyDe

This section is a short introduction to some basic concepts surrounding ForSyDe which are vital to understand how to use its implementation. If you cannot wait to get your hands dirty and begin with the implementation examples, go directly to Deep-embedded ForSyDe.

ForSyDe, which stands for Formal System Design, is a methodology aimed at raising the abstraction level in which systems (e.g. System on Chip Systems, Hardware or Software) are designed.

ForSyDe systems are modelled as networks of processes interconnected by signals. In addition, the designer is allowed to use processes belonging to different models of computation.

In order to understand how systems are modelled, it is important to get familiar with the concepts outlined above.

Signals

Signals can be intuitively defined as streams of information which flow through the different processes forming a system.

For example, this is a signal containing the first 10 positive numbers

Example 1: Signal containing the first 10 positive numbers

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10}

More formally, a signal is a sequence of events where each event has a tag and a value. In ForSyDe, the tag of an event is implicitly given by the event’s position on the list. For instance, the sample signal above is formed by integer values which are identical to the signal implicit tags.

It is important to note that signals are homogeneous (i.e. a signal cannot carry values belonging to different types)

Note: The interpretation of tags, as we will see, is determined by the model of computation used, e.g. an identical tag of two events in different signals does not necessarily imply that these events happen at the same time.

Processes

Processes are pure functions on signals, i.e. for a given set of input signals a process always gets the same set of output signals.

They can also be viewed as a black box which performs computations over its input signals and forward the results to adjacent processes through output signals.

Note that this still allows processes to have internal state. A process does not necessarily react identically the same event applied at different times. But it will produce the same, possibly infinite, output signals when confronted with identical, possibly infinite, input signals.

One of the simplest examples one can think of, is a process which merely adds one to every value in its only input signal: plus1.

Example 2: The plus1 process

plus1(<v1, v2, v3, ...>) = <v1+1, v2+1, v3+1, ...>)

Process Constructors

In ForSyDe, all processes, even plus1, must be created from process constructors. A process constructor takes zero or more functions and/or values which determine the initial state and behaviour of the process to be created.

The ForSyDe methodology offers a set of well-defined process constructors. For example, certain process constructors are aimed at creating synchronous systems. Synchronous systems are governed by a global clock and all processes consume and produce exactly one signal event in each clock-cycle.

For instance mapSY (where the suffix SY stands for SYncrhonous) is a combinational process constructor. The term combinational comes from Digital Circuit Theory. In the context of ForSyDe, a synchronous process is combinational, as opposed to sequential, if its outputs don’t depend on the history of the input signals. That is, the process is stateless, all output values can only depend on the input values consumed in the same clock cycle. mapSY takes a function f and creates a process with one input and output signal, resulting from the application of f to every value in the input.

plus1 can, in fact, be defined in terms of mapSY as plus1 = mapSY (+1).

ForSyDe also supports synchronous, sequential systems. However, it does not allow loops formed exclusively by combinational processes, also known as combinational loops, zero-delay loops or feedback loops, since their behaviour is not always decidable. Even with that, combinational loops are still possible if they contain at least one process formed by the delaySYₖ (k > 0) constructor, which is defined as follows.

delaySYₖ takes an initial value s₀ and creates a process which appends s₀, replicated k times, to its input signal. delaySY provides the basic mechanism with which to build sequential systems.

Both mapSY and delaySYₖ are considered primitive process constructors, since they cannot be defined in terms of simpler ones. Primitive constructors can be combined, forming derived process constructors. For instance, sourceSY is the result of combining delaySY₁ (normally denoted simply as delaSY) and mapSY.

sourceSY takes an initial value s₀ and a function f, and creates a sequential process with no inputs and just one output, resulting from the reiterated application of f to s₀.

For example, sourceSY(1,(+1)), is a counter with 1 as its initial value.

ForSyDe supplies many other process constructors (e.g. zipWithSY, mealySY …). However, a thoroughly description is out of the scope of this tutorial.

Models of Computation and Domain Interfaces

A model of computation (MoC), also known as computational model, establishes a set of constraints on the possible processes and signals contained by a system. A system is said to belong to certain MoC if it satisfies its constraints.

The behaviour of a process is observed in its evaluation. The evaluation is divided in atomic steps called evaluation cycles, during which the process produces and consumes signal values. MoCs specify how and when evaluation cycles are fired.

ForSyDe currently offers many MoCs, among them:

- The Synchronous MoC was already mentioned in previous section. All systems contain an implicit global clock. Its cycle matches the evaluation cycle of all the system processes, during which they must consume and produce exactly one value on every input and output signal.

- Untimed MoC. Communication between processes can be thought as a specific variant of asynchronous, blocking message passing. There is no notion of time or global clock.

Contrary to the Synchronous MoC, in which all the system processes evaluate in parallel during every cycle, untimed processes are fired individually. A process only evaluates when all their inputs have a minimum number of values ready to be read. That number may vary between inputs, but is fixed for each of them. On the other hand, the number of values produced by output signals may vary independently between evaluation cycles. - The Continuous MoC models continuous signals representing them as continuous one-variable, piecewise functions.

< (sin(x),[-10,0)), (-sin(x),[0,10)) >

ForSyDe specifies a set of process constructors for each MoC. A ForSyDe system is thus guaranteed to belong to a MoC if it was built using constructors from one of those sets.

Nevertheless, it is possible to build heterogeneous systems, i.e. systems which mix different MoCs. For that purpose, ForSyDe provides special (in the sense of belonging to any particular MoC) processes in charge of connecting two subsystems which belong to different MoCs or which have different timing specifications (e.g. two Synchronous subsystems with a different clock period).

Deep-embedded ForSyDe

As we already mentioned, ForSyDe is implemented as a Domain Specific Embedded Language (DSL) on top of Haskell. Actually, ForSyDe offers two different DSL flavours according to how signals are modelled.

-

Shallow-embedded signals (ForSyDe.Shallow.Signal) are modelled as streams of data isomorphic to lists.

data Signal a = NullS | a :- Signal aSystems built with them are unfortunately restricted to simulation, however, shallow-embedded signals provide a rapid-prototyping framework with which to experiment with models of computation.

-

Deep-embedded signals (ForSyDe.Deep.Signal) are used in a similar way to shallow-embedded signals but are modelled as an abstract data type which, transparently to the end user, keeps track of the system structure. Based on that structural information, ForSyDe’s embedded compiler can perform different analysis and transformations such as simulating the system or translating it to other target languages (e.g. VHDL and GraphML). As a drawback, the deep-embedded API can only currently build systems belonging to the Synchronous MoC and domain interfaces are not yet supported. This limitation is, however, likely to change in the future.

Using deep-embedded Signals

In this section we go through a few simple sample systems built with ForSyDe’s deep-embedded API. We will create both combinational and sequential systems all belonging to the Synchronous MoC (the only MoC currently supported by this API).

Combinational Systems

A system or process is combinational if its outputs are stateless, i.e. they don’t depend on past system events.

A naive combinational system: plus1

We are going to implement plus1, ForSyDe’s Hello World, a system with takes integer values, adds 1 to them and forwards the result through its output signal.

As we mentioned previously, the plus1 process can be created in terms of the mapSY process constructor. Here is the signature of mapSY in the deep-embedded API.

mapSY :: (ProcType a, ProcType b) =>

ProcId -> ProcFun (a -> b) -> Signal a -> Signal b

mapSY works similarly to Haskell’s map function. It creates a process which applies a function to every value in a signal. Let’s have a closer look at its arguments.

ProcId- The process identifier, simply a textual tag which univocally identifies the process created (

type ProcId = String). ProcFun (a->b)- A process function. The function which will be applied to every element in the input signal. In the case of plus1 we will need a function computationally equivalent to

(+1). Bothaandbmust be instances ofProcType(read Process Type).ProcTypeis used by ForSyDe's embedded compiler to extract type and structure information of expressions. Signal a- Input signal.

Signal b- Output signal.

Now, we are ready to start implementing plus1.

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell #-}

module Plus1 where

import ForSyDe

import Data.Int (Int32)

We need to import ForSyDe’s library and Int32. Since deep-embedded systems might be later translated to hardware, it is required to be specific about the size of integers used (the size of Int is platform-specific). Additionally, in all ForSyDe deep-embedded designs we need to tell GHC to enable the Template Haskell (TH) extension, here is why:

-- A process function which adds one to its input

addOnef :: ProcFun (Int32 -> Int32)

addOnef = $(newProcFun [d|addOnef :: Int32 -> Int32

addOnef n = n + 1 |])

In the code above, we declared the ProcFun needed by mapSY. It simply takes an Int32 value and adds 1 to it.

Instead of creating a specific DSL to express computations in the deep-embedded model, ForSyDe uses TH to allow using plain Haskell. In principle, ProcFuns can make use of any Haskell feature supported by TH. However, such features might not be supported or make sense for certain backends (e.g. lists and thus, list comprehensions, are difficult to support in VHDL). Thus, in this tutorial we will create systems which are compatible with every backend. For example, writing addOnef = (+1) instead of addOnef n = n+1 is more compact, however the VHDL backend does not currently support sections nor points-free notation.

In order to use ForSyDe it is not vital to understand what is really happening, but, for those curious about it, here is how the TH trick works. First, the [d| .. |] brackets enclosing the function declaration lift its AST (Abstract Syntax Tree). Then, the AST is used by newProcFun to splice (expand in TH’s terminology) a ProcFun. It is important to note that everything happens at compile-time.

Here is the rest of the system definition.

-- System function (simply a process in this case) which uses addOnef

plus1Proc :: Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32

plus1Proc = mapSY "plus1Proc" addOnef

-- System definition associated to the system function

plus1SysDef :: SysDef (Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32)

plus1SysDef = newSysDef plus1Proc "plus1" ["inSignal"] ["outSignal"]

First, we use mapSY to create process. Then we create the final definition of the plus1 system with newSysDef. Here is its type signature.

newSysDef :: (SysFun f) => f -> SysId -> [PortId] -> [PortId] -> SysDef f

f- A SysFun (system function) describing the system. It results from the combination of one or more processes. ForSyDe uses a trick similar to

Text.Printfin order to emulate variadic functions (different systems are obviously allowed to have different number of inputs and outputs). SysId- Textual tag identifying the system.

type !SysId = String. [PortId]- List of port identifiers for the system inputs and outputs.

type !PortId = String.

Now we can simulate our system, or, as we will see later on, translate it to VHDL or GraphML.

simulate :: SysFunToSimFun sysFun simFun => SysDef sysFun -> simFun

simulate transforms our system definition into a list-based function with the help of a multiparameter typeclass, SysFunToSimFun, in charge of implementing the type-level translation of the system signals to lists.

$ ghci Plus1.hs

*Plus1> let simPlus1 = simulate plus1SysDef

*Plus1> :t simPlus1

simPlus1 :: [Int32] -> [Int32]

*Plus1> simPlus1 [1..10]

[2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]

Simulation is lazy, allowing to work with infinite signals.

*Plus1> take 10 $ simPlus1 [1,1..]

[2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2]

It is important to remark that ForSyDe does not support systems containing combinational loops. If such a loop is found, an error will be reported.

For example, here is a system containing a combinational loop, built with a mutually recursive call between two processes adding one to their inputs.

combLoopSysDef :: SysDef (Signal Int32)

combLoopSysDef = newSysDef s "combLoop" [] ["out"]

where s = mapSY "addOne1" addOnef s'

s' = mapSY "addOne2" addOnef s

As we mentioned, combLoopSysDef cannot be simulated.

*Plus1> simulate combLoopSysDef

*** Exception: detected combinational loop

Keypad encoder

Here is a slightly more complex example. We have a keypad with 4 arrow buttons connected to our synchronous system. The key-presses are sent in the form of a 4-bit vector. Each bit indicates whether the corresponding button is pressed (high value) or not (low value) according to the diagram below.

In order to work more comfortably and forget about multiple key-strokes at once, we want to encode each key-press event with a specific Haskell type: data Direction = Left | Down | Right | Up.

Of course, keys are not necessarily pressed all the time. Thus, instead of encoding the input vector into a signal of Direction we will output signals of AbstExt Direction.

data AbstExt a = Abst | Prst a

AbstExt (read absent-extended) is ForSyDe’s equivalent to the popular Haskell type Maybe. It is used to introduce absent values in signals, in our particular case it will denote an absence of key presses.

Here is the definition of Direction together with the necessary imports for the definition of the whole system.

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell, DeriveDataTypeable #-}

module Encoder where

import ForSyDe

import Language.Haskell.TH.Lift (deriveLift1)

import Prelude hiding (Left, Right)

import Data.Generics (Data,Typeable)

import Data.Param.FSVec

import Data.TypeLevel.Num hiding ((==))

data Direction = Left | Down | Right | Up

deriving (Typeable, Data, Show)

$(deriveLift1 ''Direction)

There are a few things worth remarking

- Since we are defining new constructors named

LeftandRight, to avoid clashes with the identically-named constructors ofEitherwe hide their import from thePrelude. -

We are defining a custom enumerated datatype

Direction(more formally, a datatype with data constructors whose arity is zero in all cases), whose values will be carried by system signals. All the values used in a system, andDirectionin particular, must be instances of the private typeclassProcType.class (Data a, Lift a) => ProcType a -- Some existing (overlapping) instances of ProcType instance (Data a, Lift a) => ProcType a instance ProcType a => ProcType (AbstExt a) instance (ProcType a, ProcType b) => ProcType (a,b) ...The

ProcTypeconstraint is required, among other reasons, to provide type and structural information of datatypes to ForSyDe’s embedded compiler. The overlapping instances are needed to obtain datatype information regardless of the nesting of values in other supported datastructures.Due to the

(Data a, Lift a) => ProcType ainstance all we need to do in order to use our custom enumerated datatypes with ForSyDe is creating instances ofData(which implicitly requires an instantiation ofTypeable) and Template Haskell’sLiftclass.Fortunately, thanks to a GHC extension it is possible to derive instances for

TypeableandData(hence theDeriveDataTypeablelanguage pragma). Additionally, ForSyDe provides a Template Haskell moduleLanguage.Haskell.TH.Liftto automatically generate instances ofLift. In this case, since we needed to instantiate a single datatype, we usedderiveLift1. - The rest of the imports (

Data.Param.FSVecandData.TypeLevel.Num) come from the parameterized-data and type-level packages in order to support fixed-sized vectors.

Here is the code of the process function, needed to encode the button presses:

encoderFun :: ProcFun (FSVec D4 Bit -> AbstExt Direction)

encoderFun = $(newProcFun

[d| encode :: FSVec D4 Bit -> AbstExt Direction

encode v = if v ! d0 == H then Prst Left else

if v ! d1 == H then Prst Down else

if v ! d2 == H then Prst Right else

if v ! d3 == H then Prst Up else Abst |])

The code should be self-explanatory, it makes use of the type ForSyDe.Bit.Bit, with data constructors L (low) and H (high), and of vectors of size 4 (hence the D4 type parameter). In order to get a deeper insight on how FSVecs work, check FSVecs: Vectors parameterized in size. It is important to note that the system does not take simultaneous key-strokes in account, choosing the direction with higher precedence (i.e. situated in the outermost if expression). Also, using pattern matching with multiple function clauses instead of nested if expressions would had been more clear. However, the VHDL backend currently only supports one clause.

Here is the remaining code needed to build the rest of the system.

encoderProc :: Signal (FSVec D4 Bit) -> Signal (AbstExt Direction)

encoderProc = mapSY "encoder" encoderFun

encoderSysDef :: SysDef (Signal (FSVec D4 Bit) -> Signal (AbstExt Direction))

encoderSysDef = newSysDef encoderProc "KeypadEncoder" ["arrowBits"] ["direction"]

Finally, we can evaluate some simulations.

$ ghci -XTemplateHaskell Encoder.hs

*Encoder> let simEncoder = simulate encoderSysDef

*Encoder> :t simEncoder

simEncoder :: [FSVec D4 Bit] -> [AbstExt Direction]

*Encoder> simEncoder [$(vectorTH [L,H,L,L]), $(vectorTH [L,L,L,L])]

[Down,_]

Sequential Systems

Now we are going to have a look at a couple of sequential systems, whose outputs, contrary to combinational systems, can depend on the system history (i.e. can have a state).

A naive sequential system: counter

Our goal is to generate a signal whose values match its tags or, more intuitively, a counter from 1 to infinity.

This is clearly a sequential system since its output signal is not stateless, each output value depends on the previous one.

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell #-}

module Counter where

import ForSyDe

import Data.Int (Int32)

import Plus1 (addOnef)

counterProc :: Signal Int32

counterProc = out'

where out = mapSY "addOneProc" addOnef out'

out' = delaySY "delayOne" 1 out

counterSysDef :: SysDef (Signal Int32)

counterSysDef = newSysDef counterProc "counter" [] ["count"]

We reuse addOnef from previous examples. The counter is built by the mutually recursive calls of mapSY and delaySY which should be interpreted as parallel equations.

Again, we can lazily simulate the system.

$ ghci Counter.hs

*Counter> :t simulate counterSysDef

simulate counterSysDef :: [Int32]

*Plus1> simulate counterSysDef

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17

^C Interrupted

Actually, the definition of counterProc can be simplified by using sourceSY, getting the following equivalent declaration.

counterProc :: Signal Int32

counterProc = sourceSY "counterProc" addOnef 1

Serial full adder

A serial full adder which adds two streams of bits is a, still simple, but more elaborated example of a sequential system. Our system will receive pairs of bits which will be added together, taking the resulting carry of last cycle in account.

We are going to implement it as a Mealy FSM (Finite State Machine) following the diagram below.

ForSyDe provides derived process constructors to implement FSMs, in this case we will be using mealySY.

mealySY :: (ProcType c, ProcType b, ProcType a) =>

ProcId

-> ProcFun (a -> b -> a)

-> ProcFun (a -> b -> c)

-> a

-> Signal b

-> Signal c

ProcId- The process identifier, used in the same way as in the rest of the process constructors (e.g. mapSY and delaySY).

ProcFun (a- > b -> a)- A process function in charge of calculating next state based on current state and current input.

ProcFun (a -> b -> c)- A process function in charge of calculating current output based on current state and current input.

a- Initial state.

Signal b- Input Signal.

Signal c- Output Signal.

Here is the Haskell code, which should be straightforward to understand.

{-# LANGUAGE TemplateHaskell #-}

module FullAdder where

import ForSyDe

faNextState :: ProcFun (Bit -> (Bit,Bit) -> Bit)

faNextState = $(newProcFun

[d| faNextState :: Bit -> (Bit,Bit) -> Bit

faNextState st input =

if st == L then

case input of

(H, H) -> H

_ -> L

else

case input of

(L,L) -> L

_ -> H

|])

faOut :: ProcFun (Bit -> (Bit,Bit) -> Bit)

faOut= $(newProcFun

[d| faOut :: Bit -> (Bit,Bit) -> Bit

faOut st input =

if st == L then

case input of

(L, L) -> L

(L, H) -> H

(H, L) -> H

(H, H) -> L

else

case input of

(L, L) -> H

(L, H) -> L

(H, L) -> L

(H, H) -> H

|])

faProc :: Signal (Bit,Bit) -> Signal Bit

faProc = mealySY "addProc" faNextState faOut L

faSysDef :: SysDef (Signal (Bit,Bit) -> Signal Bit)

faSysDef = newSysDef faProc "fullAdder" ["op1", "op2"] ["res"]

Here is a little test.

*FullAdder> let simfa = simulate faSysDef

*FullAdder> simfa [(L,L),(L,H),(H,H),(L,L)]

[L,H,L,H]

*FullAdder>

Using components

A desired characteristic of any system design language is the possibility of creating hierarchical models.

In ForSyDe’s deep-embedded DSL, hierarchical design is implemented through components, let’s see an example.

The system above which, admittedly, would not be of much use in the real world, adds 4 to its input in serial steps of 1.

Instead of creating 4 different processes and connecting them together, we can reuse the design of plus1 placing 4 identical components.

ForSyDe provides a primitive to create components or instances of a system: instantiate.

instantiate :: (SysFun f) => ProcId -> SysDef f -> f

instantiate creates a component out of a system definition. A component can be considered a special process (hence the ProcId parameter) containing an instance of its parent system (the system from which it is created).

Instances behave identically to their parents and can be combined with other system processes.

For example, here we create and simulate an instance of plus1

$ ghci Plus1.hs

*Plus1> :t plus1SysDef

plus1SysDef :: SysDef (Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32)

*Plus1> let plus1Comp1 = instantiate "plus1_1" plus1SysDef

*Plus1> :t plus1Comp1

plus1SysDef :: Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32

*Plus1> let nestedPlus1 = newSysDef plus1Comp1 "nestedPlus1" ["in1"] ["out1"]

*Plus1> simulate nestedPlus1 $ [1,2,3,4]

[2,3,4,5]

And here is the definition of the AddFour system.

module AddFour where

import Plus1 (plus1SysDef)

import ForSyDe

import Data.Int (Int32)

addFourProc :: Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32

addFourProc = plus1Comp "plus1_1" .

plus1Comp "plus1_2" .

plus1Comp "plus1_3" .

plus1Comp "plus1_4"

where plus1Comp id = instantiate id plus1SysDef

addFourSysDef :: SysDef (Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32)

addFourSysDef = newSysDef addFourProc "addFour" ["in1"] ["out1"]

Components, just like any other process, are functions over signals. This allows using all the combinatorial power of Haskell. In this particular case we have just used function composition.

Here is the general workflow of ForSyDe modelling, including the use of components.

- The designer describes computations using process functions (

ProcFuns). - Those process functions, possibly with other constants, are passed to process constructors in order to build processes which are combined together, creating the main process function.

- The system function is transformed into a system definition by newSysDef.

- The system definition can be

- passed to ForSyDe’s embedded compiler, capable of simulating or translating it to other target languages (VHDL or GraphML at the time being).

- used to create components, bringing us back to step 2.

The VHDL Backend

ForSyDe’s embedded compiler is able to translate system definitions to VHDL. That is done through the writeVHDL* functions.

writeVHDL :: SysDef a -> IO ()

writeVHDLOps :: VHDLOps -> SysDef a -> IO ()

For example, this is how we would generate the VHDL definition of AddFour and write it to disk.

$ ghci AddFour.hs

*AddFour> writeVHDL addFourSysDef

*AddFour> :q

Leaving GHCi.

$ ls -R addFour

vhdl

addFour/vhdl:

addFour_lib work

addFour/vhdl/addFour_lib:

addFour_lib.vhd

addFour/vhdl/work:

addFour.vhd plus1.vhd

Here is a diagram of the filetree generated for addFour.

writeVHDL generates a VHDL filetree pending from current working directory. Assuming $SYSNAME is the system’s name (addFour in this particular case):

- The main VHDL entity and architecture is written in

$SYSNAME/vhdl/work/$SYSNAME.vhdl. -

The VHDL translation of other systems included through component instantiation is also written under

$SYSNAME/vhdl/work/.In the case of the addFour system, the compiler also generates the file

plus1.vhd. -

A global VHDL library,

forsyde_lib.vhd, is bundled with ForSyDe’s distribution and contains the translation of basic monomorphic Haskell types to VHDL.It is installed under the data directory of ForSyDe’s Cabal package, whose location is system-dependent.

-

Since VHDL lacks support for

parametric polymorphism, the translation of polymorphic types and functions is done on a per-system basis (i.e. each different possible monotype of a polymorphic Haskell type triggers a different translation).Thus, the result of that translation is put in

$SYSNAME/vhdl/lib/$SYSNAME_lib.vhdand notforsyde_lib.vhd.It is important to remember that, even if ForSyDe signals are polymorphic and

ProcFunscan include any Haskell function definition, some backends might be limited. In the case of the VHDL backend:- Accepted Signal types:

Signal ais a valid signal for the VHDL backend ifabelongs to:- Primitive types: Data.Int{8, 16, 32}, Bool, ForSyDe.Bit.

- Custom types: enumerated.

- The following containers, which can hold any primitive or custom type and can be unrestrictively nested:

Data.Param.FSVec, tuples of unlimited size (in practice, the upper limit is Haskell-compiler dependent).

- Although this will hopefully change in the future, the declarations contained by

ProcFunsmust be fairly simple. For instance:- Points-free notation is not admitted.

- They can only contain a clause, multiple clauses are not accepted.

- Accepted Signal types:

Getting back to the function interface of the VHDL backend, it is possible to provide certain compilation options, namely to integrate Altera’s Quartus II and Modelsim in our workflow. For that purpose we will use writeVHDLOps.

For example, we can generate a Quartus II project and compile the generated VHDL code setting certain configuration options such as the pin-mapping and the FGPA model to be used.

compileQuartus :: IO ()

compileQuartus = writeVHDLOps vhdlOps addFourSysDef

where vhdlOps = defaultVHDLOps{execQuartus=Just quartusOps}

quartusOps = QuartusOps{action=FullCompilation,

fMax=Just 50, -- in MHz

fpgaFamiliyDevice=Just ("CycloneII",

Just "EP2C35F672C6"),

-- Three sample pin assignments

pinAssigs=[("in1[0]", "PIN_W1"),

("in1[1]", "PIN_W2"),

("in1[2]", "PIN_W3")]}

The code above generates the VHDL code for the addFour system, subsequently creating a Quartus project and running a full compilation of the project. We set a minimum acceptable clock frequency of 50 MHz, the FPGA family (CycloneII), specific device (EP2C35F672C6) and some pin assignments, which, for briefness’ sake are not sufficient.

It is important to note that, when needed, Quartus will split input and output port identifiers into several logical names corresponding to individual bits (e.g in1[0]). Thus, it might be necessary to open Quartus in order to find out what logical names to use in pin assignments.

In addition to Quartus II, the VHDL backend is able to interface with ModelSim. For example, the following function shows how can we automatically compile the generated VHDL code with ModelSim.

compileModelSim :: IO ()

compileModelSim = writeVHDLOps vhdlOps addFourSysDef

where vhdlOps = defaultVHDLOps{compileModelsim=True}

It is also possible to run test benches in ModelSim.

writeAndModelsimVHDL :: (SysFunToIOSimFun sysF simF) =>

Maybe Int -> SysDef sysF -> simF

writeAndModelsimVHDLOps :: (SysFunToIOSimFun sysF simF) =>

VHDLOps -> Maybe Int -> SysDef sysF -> simF

Here are two examples:

$ ghci AddFour.hs

*AddFour> let vhdlSim = writeAndModelsimVHDL Nothing addFourSysDef

*AddFour> :t vhdlSim

vhdlSim :: [Int32] -> IO [Int32]

*AddFour> vhdlSim [1..10]

[4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]

In the example above, we simulate addFour without supplying a limit in the number of cycles to simulate. writeAndModelsimVHDL is strict, so, without a limit it will only work with finite input stimuli.

$ ghci Counter.hs

*Counter> writeAndModelsimVHDL (Just 20) counterSysDef

[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

In this case the system does not have any inputs and thus the simulation implicitly results in infinite output stimuli. Thus, it is necessary to set a limit in the number of cycles to simulate.

In a general way, the writeAndModelsimVHDL* functions, generate a simulation function which will

- Generate a VHDL model (implicitly using the

writeVHDL*functions). - Compile the resulting model with ModelSim.

- Marshal the provided input stimuli from Haskell to VHDL and generate a testbench in

$SYSNAME/vhdl/test/$SYSNAME_tb.vhd. - Simulate the testbench with ModelSim and unmarshal the results back to Haskell.

writeAndModelsimVHDL* give equivalent results to simulate, with a few caveats.

writeAndModelsimVHDL*, unlike simulate, are strict, and thus do not support infinite stimuli. For that reason, it is possible to set the number of cycles to simulate (Maybe Intparameter).writeAndModelsimVHDL*, provideIO(i.e. side-effect prone) simulation functions whereas simulate is pure.writeAndModelsimVHDL*suffer all the limitations of the VHDL backend whereas simulate can cope with any system.

The GraphML Backend

It is possible to use ForSyDe’s GraphML backend in order to

- Generate an XML-based intermediate representation of a system for further processing.

- Obtain system diagrams.

ForSyDe provides the following functions, similar to the ones of the VHDL backend.

writeGraphML :: SysDef a -> IO ()

writeGraphMLOps :: GraphMLOps -> SysDef a -> IO ()

For example, here is how we would generate the GraphML translation of addFour

$ ghci AddFour.hs

*AddFour> writeGraphML addFourSysDef

*AddFour> :q

Leaving GHCi.

$ ls -R addFour

graphml

addFour/graphml:

addFour.graphml plus1.graphml

As we can see, a .graphml file is generated for each system involved. In this case, one for the main system (addFour.graphml) and another one for plus1 which was instantiated by addFour.

In order to embed ForSyDe metainformation, the GraphML backend makes use of the following GraphML-Attributes:

<key id="process_type" for="node" attr.name="process_type" attr.type="string"/>

<key id="value_arg" for="node" attr.name="value_arg" attr.type="string"/>

<key id="procfun_arg" for="node" attr.name="procfun_arg" attr.type="string"/>

<key id="instance_parent" for="node" attr.name="instance_parent" attr.type="string"/>

The keys above are used to tag nodes in different ways.

process_typeindicates what process constructor was used to create a process node or if the node is an input or output port.value_argcontains a value passed to a process constructor.procfun_argcontains a value passed to a process constructor.instance_parentis specific to component nodes and indicates the name of the parent system from which the component was instanciated.

Obtaining diagrams of ForSyDe

The GraphML definition does not provide a way to specify the graphical representation of graphs (e.g. edge and node shapes, colours, textual tags …)

For that reason, yWorks, a company offering graph visualization products, created yFiles-GraphML, an extension to the GraphML schema which adds graphical information. yWorks also distributes yEd, a free (as in beer) multiplatform graph editor with impressive automatic layout features.

Here is an example on how to generate and edit yFiles-GraphML diagrams from ForSyDe systems. For this purpose, we will use our counter system.

$ ghci Counter.hs

*Counter> writeGraphMLOps defaultGraphMLOps{yFilesMarkup=True} counterSysDef

*Counter> :q

$ ls -R counter

graphml

counter/graphml:

counter.graphml sourceSY_counterProc.graphml

sourceSY_counterProc.graphml contains the sourceSY process used in the counter. Let’s view its representation with yEd.

This is the unorganized representation we get right after opening sourceSY_counterProc.graphml with yEd.

All nodes are overlapped because the GraphML-yFiles backend does not perform any kind of node placement nor edge routing. yEd, however, does a very good job in this regard.

Before running a layout algorithm it is convenient to set port constraints on the graph nodes. This is a workaround to make yEd faithfully represent shared signals (signals coming from the same process output), otherwise yEd will treat them as different outputs. The GraphML format (and GraphML-yFiles) allows edge sharing through the use of ports, however, yEd does not currently respect them. Our current solution is to set a location for the edge ends in the GraphML backend and lock that location through yEd port constraints.

In order to set the port constraints we will go to Tools -> Constraints -> Port Constraints.

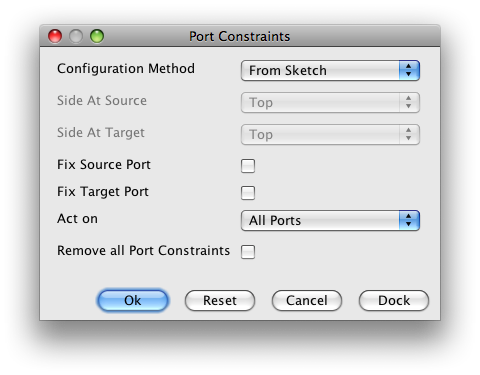

The port constraints menu will initially look like this.

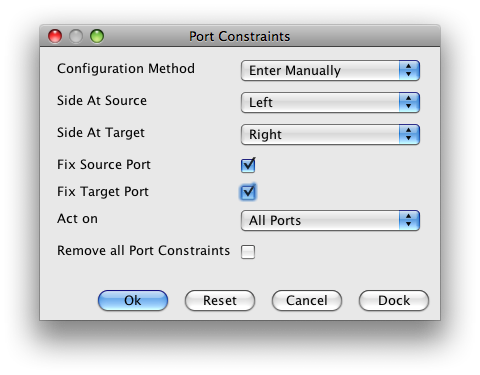

These are the options we need to set in order to fix all ports. Remember to click on OK after setting them.

It is important to note that due to a bug in yFiles format it is not possible to save port constraints in .graphml files. Thus, we will need to reset the port constraints every time a file is reopened.

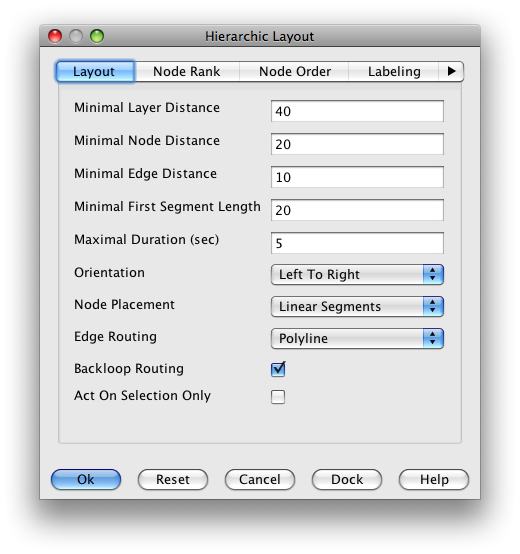

Now we are ready to run an automatic layout algorithm. The generated GraphML-yFiles graph is prepared to be displayed from left to right. The hierarchical layout (Layout -> Hierarchical -> Classic) seems to give the best results for system diagrams. It is important to set the Orientation to Left to Right and allow Backloop Routing.

After clicking on OK, the system diagram should look like this:

GraphML limitations

Unfortunately, GraphML nor yFiles-GraphML + yEd suit all ForSyDe needs:

- yFiles does not respect GraphML ports (source signal sharing). We provide a workaround based on precalculate the location of edge ends plus yEd routing port constraints (which unfortunately cannot be saved).

- yEd wipes out external

<data>tags (external GraphML attributes). That includes ForSyDe’s metainformation, which will be lost after editing the graph with yEd. - GraphML nor yFiles-GraphML explicitly support subgraphs but not subgraph sharing (components). Our solution is to use external

<data>tags indicating parent systems in instance nodes. However, yEd is obviously unaware of that trick, not being able to offer hierarchical browsing.

Using shallow-embedded Signals

As it was previously mentioned, ForSyDe offers a flavour of signals called shallow-embedded signals, modelled as streams of data:

data Signal a = NullS | a :- Signal a

This representation offers some advantages:

- Rapid prototyping of systems.

- It is easy to include new MoCs.

- It supports all the MoCs covered by ForSyDe (Synchronous, Untimed and Continuous).

Shallow-embedded signals also present some disadvantages:

- Systems built with them can only be simulated. Shallow-embedded signals don’t contain any structural information. Thus, the models resulting from them cannot be analyzed or compiled to other target languages.

- No support for components. However, they are not really needed, components are not useful for simulation and reusability can be achieved by function refactoring.

Here is the implementation of plus1 using shallow-embedded signals.

module Plus1Shallow where

import ForSyDe.Shallow

import Data.Int(Int32)

plus1 :: Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32

plus1 = mapSY (+1)

The system can be simulated directly simply by calling plus1.

$ ghci Plus1Shallow.hs

*Plus1Shallow> :t signal

signal :: [a] -> Signal a

*Plus1Shallow> plus1 (signal [1..10])

{2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11}

We can also integrate deep-embedded models into shallow-embedded ones by using simulate, signal and fromSignal (the inverse of signal). In the example below, we use the deep-embedded addFour system and the shallow-embedded plus1 to build plus5

module Plus5 where

import Plus1Shallow

import AddFour

import ForSyDe (simulate)

import ForSyDe.Shallow

import Data.Int (Int32)

plus5 :: Signal Int32 -> Signal Int32

plus5 = plus1 . signal . simulate addFourSysDef . fromSignal

$ ghci Plus5.hs

*Plus5> plus5 (signal [1..10])

{6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15}

Appendices

FSVecs: Vectors parameterized in size

Goal

We would like to numerically parameterize vectors using their length in order to implement fixed-sized vectors (FSVec). Ideally, we would like to be able to implement something similar to this:

v :: FSVec 23 Int -- Not Haskell

v would be a a vector containing 23 Ints. Note it is not possible to directly do this in Haskell.

The vector concatenation function would be something along the lines of:

(++) :: FSVec s1 a -> FSVec s2 a -> FSVec (s1+s2) a -- Again, not valid Haskell

We would also like to establish static security constraints on functions. Those constrains would be checked at compile time guaranteeing a correct behavior during runtime. For instance.

head :: FSVec (s > 0) a -> FSVec (s - 1) a -- Not Haskell

However, Haskell does not support dependent types (a numerically parameterized-vector is in practice a dependent type) nor type-level lambdas directly. Yet, it is still possible to implement our FSVec type using Haskell plus a few GHC extensions.

How?

Before diving into the details, let me spoil the final result:

v :: FSVec D23 Int

(++) :: (Nat s1, Nat s2, Add s1 s2 s3) => FSVec s1 a -> FSVec s2 a -> FSVec s3 a

head :: Pos s => FSVec s a -> a

The code is a bit more verbose that the pseudo-Haskell code of previous section, but note that it is Haskell code (using the Multiparameter class extension).

The trick is to emulate the parameters using type-level decimal numerals. But, What is that?

Type-level decimal numerals

We already mentioned that the trick is to use types to represent the size of the vector. So, we want a type parameter to represent a number, but, How?

-- Numerical digits

data D0 -- empty type (supported by a EmptyDataDecls GHC extension,

-- we could have included a phony constructor otherwise)

data D1

data D2

..

data D9

data a :* b -- connective to build multidigit numerals (empty again)

-- note that the type constructor is infix (GHC TypeOperators extension)

Using the definitions above we can represent arbitrarily-sized natural numbers. Some examples:

| Number | Type-level representation |

| 0 | D0 |

| 13 | D1 :* D3 |

| 1024 | D1 :* D0 :* D2 :* D4 |

It seems sensible, but very verbose. It would certainly be nicer to be able to express 0 as D0, 13 as D13 and so on.

We solved the problem by using Template Haskell to generate type synonyms (aliases) up to D5000. The same trick was used to emulate binaries (up to B10000000000), octals (up to O10000) and hexadecimals (up to H1000):

$ ghci -XTypeOperators -XFlexibleContexts # Extensions used in different parts of this appendix

Prelude> :m +Data.TypeLevel

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :i D124

type D124 = (D1 :* D2) :* D4

-- Defined in Data.TypeLevel.Num.Aliases

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :i HFF

type HFF = (D2 :* D5) :* D5

-- Defined in Data.TypeLevel.Num.Aliases

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :i B101

type B101 = D5 -- Defined in Data.TypeLevel.Num.Aliases

Of course, if you want to use a numeral which is out of the aliases range, the only option is to use the verbose decimal representation (it shouldn’t be the normal case though)

Similarly to D13, D124 … undercase value-level aliases (d12, d123, .. declared as undefined) are generated in order to create type-level values.

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :i d123

d123 :: (D1 :* D2) :* D3 -- Defined in Data.TypeLevel.Num.Aliases

Fair enough. However, you might already have guessed that :* can be used to construct ambiguous or not-normalized numerals, for instance:

D0 :* D0 :* D1 -- numeral with trailing zeros

(D1 :* D0) :* (D2 :* D2) -- malformed numeral

Now is when the natural (Nat) and positive (Pos) type-classes get in the game. We are going to omit the instances but, trust us, they guarantee that numerals are well-formed:

class Nat n where

toNum :: Num a => n -> a

class Nat n => Pos n

toNum allows to pass the type-level numeral to value-level.

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> toNum d123

123

-- a non-normalized numeral

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> toNum (undefined :: D0 :* D1)

<interactive>:1:0:

No instance for (Data.TypeLevel.Num.Sets.PosI D0)

arising from a use of `toNum' at <interactive>:1:0-28

Possible fix:

add an instance declaration for (Data.TypeLevel.Num.Sets.PosI D0)

In the expression: toNum (undefined :: D0 :* D1)

In the definition of `it': it = toNum (undefined :: D0 :* D1)

Based on the numerical representation we created, and using multiparameter type-classes, we can define type-level operations. The operations supported right now are:

- Arithmetic: Successor, Predecesor, Addition, Subtraction, Multiplication, Division, Modulus, Greatest Common Divisor, Exponentiation and Logarithm.

- Comparison: trichotomy classification,

(<),(>),(<=),(>=),(==), Minimum and Maximum.

Some examples:

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :i Data.TypeLevel.divMod

Data.TypeLevel.divMod :: (DivMod x y q r) => x -> y -> (q, r)

-- Defined in Data.TypeLevel.Num.Ops

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> d23 `Data.TypeLevel.divMod` d2

(11,1)

Note that the resulting type is calculated at compile time:

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :t d23 `Data.TypeLevel.divMod` d2

d23 `Data.TypeLevel.divMod` d2 :: (D1 :* D1, D1)

d23 `Data.TypeLevel.divMod` d2 :: (D1 :* D1, D1)

Note as well that the operations are consistent, we cannot, for instance, calculate the predecessor of zero:

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> Data.TypeLevel.pred d0

<interactive>:1:0:

No instances for (Data.TypeLevel.Num.Ops.Failure

(Data.TypeLevel.Num.Ops.PredecessorOfZeroError x),

[..]

We can even add constraints to our own functions. For instance, we want to guarantee (at compilation time) that a type-level numeral number is lower than 6 and greater than 3.

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> let check :: (Nat x, x :<: D6, x :;>: D3, Num a) => x -> a; check n = toNum n

For example, 2 does not meet the constraints.

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> check d2

<interactive>:1:0:

Couldn't match expected type `CGT' against inferred type `CLT'

[..]

Whereas 4 does

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> check d4

4

Fixed Sized Vectors themselves

Getting back to fixed-sized vectors themselves, FSVec offers a reasonably rich vector API based on type-level numerals.

For example, we can safely access the elements of a vector without the risk of getting out-of-bounds errors.

(!) :: (Pos s, Nat i, i :<: s) => FSVec s a -> i -> a

The best part of it is that the bound checks are performed on the type level at compilation time, not adding any overhead to the execution of our code.

Prelude Data.TypeLevel> :m +Data.Param.FSVec

Prelude Data.TypeLevel Data.Param.FSVec> $(vectorTH [1::Int,2,3]) ! d0

1

Prelude Data.TypeLevel Data.Param.FSVec> $(vectorTH [1::Int,2,3]) ! d7

<interactive>:1:0:

Couldn't match expected type `LT' against inferred type `GT'

When using functional dependencies to combine

Trich D7 D3 GT,

[..]

vectorTH is a Template Haskell function to create vectors out of lists, we will get back to why TH is needed later. d0 and d7 are declared as undefined (bottom) and force the inference of the D0 and D7 type-level values. Note that the explicit type signatures are needed due to Haskell’s monomorphism restriction, in the general non-interactive code does not need this kind of type annotations.

Warning

Using numerical literals instead of the undefined values (e.g. 0 and 7 instead of d0 and d7) is a very common error. Here are two further examples using head.

Prelude Data.TypeLevel Data.Param.FSVec> Data.Param.FSVec.head $(vectorTH [1::Int,2,3])

1

Prelude Data.TypeLevel Data.Param.FSVec> Data.Param.FSVec.head empty

<interactive>:1:0:

No instance for (Data.TypeLevel.Num.Sets.PosI D0)

arising from a use of `Data.Param.FSVec.head'

Again, attempting to obtain the head of an empty vector triggers a compile-time error.

Even if FSVec offers many nice features, it also has a few problems.

FSVec issues

There are a few caveats the designer should be aware of:

-

Some functions such as filter cannot be implemented.

One can think about something along the lines of:

filter :: (a -> Bool) -> FSVec s a -> FSVec s2 aHowever, the size of the output vector (

s2) cannot be precalculated statically. - Since

FSVecis an abstract data type, pattern matching is lost, but that is the general case in vector implementations. -

It is difficult to build a vector from a list. Again, the first thing one would think of would be

vector :: Nat s => [a] -> FSVec s aHowever, since s would be a different type depending on the length of

[a], this is not a valid Haskell function. s is existentially quantified, a feature not supported directly by Haskell98. - In addition, since the list-length is a run-time condition, it is impossible to guess at compile time.

However, there are a few workarounds which are already included in the library:

-

As suggested in Eaton’s Statically Typed Linear Algebra in Haskell, emulate an existential through CPS (continuation passing style). CPS is a style of programming where functions never return values, but instead take an extra parameter which they give their result to.

vectorCPS :: Nat s => vectorCPS :: [a] -> (forall s. Nat s => FSVec s a -> w) -> wNote that the

forallkeyword is due to usingRank2types to emulate the existential. You don’t really need to understand how they work but just know to usevectorCPS. Here is an example:$ ghci Prelude> :m +Data.Param Prelude Data.Param> (vectorCPS [1,2,3,4]) Data.Param.length 4

Note that length is passed to the result of vectorCPS and not the other way around.

-

Unsafely provide the length of the resulting vector:

unsafeVector :: Nat s => s -> [a] -> FSVec s aunsafeVectordoes not suffer the “existential type” problem ofvectorCPS, however it can happen that the dynamic length of the list does not match the provided length (that is why the function name has an “unsafe” prefix). Furthermore if that is the case, we will only be able to know at runtime.Prelude Data.Param> :m +Data.TypeLevel Prelude Data.Param Data.TypeLevel> unsafeVector d8 [1,2] *** Exception: unsafeVector: dynamic/static length mismatch Prelude Data.Param Data.TypeLevel> unsafeVector d2 [1,2] <1,2> -

Template Haskell. This is the preferred solution. The only problem is that, of course, the TH extension is required (but we already had that dependency in ForSyDe) and you can only use it with lists which are available at compile time (which, for the general case of ForSyDe designs should not be a problem).

$ ghci -XTemplateHaskell Prelude> :m +Data.Param Prelude Data.Param> $(vectorTH [1 :: Int,2,3,4]) Prelude Data.Param> :t $(vectorTH [1 :: Int,2,3,4]) $(vectorTH [1 :: Int,2,3,4]) :: (Num t) => FSVec Data.TypeLevel.Num.Reps.D4 t